The previous post on Scotland’s food and drink highlights the fact that what people ate was very much dependent on what people could grow, according to climate, topography and soil type.

In Kilbride, County of Bute, “the soil is hard and stony. Most of the farms lying on the declivity of hills, the best prepared land scarce yields two returns. To supply the deficiency of corn, the inhabitants plant great quantities of potatoes, which are their principal food for 9 months in the year.” (OSA, Vol. VIII, 1793, p. 578)

In contrast, the soil in the parish of North Berwick, County of Haddington, was “, in general, rich, fertile, and well cultivated, producing large crops of all the different grains sown in Scotland, as wheat, barley, oats, pease and beans. No hemp is raised, and the quantity of flax is inconsiderable, being only for private use. Turnips are cultivated, but not to a great extent, as the farmers reckon the ground to be in general too strong and wet for that useful plant, and on that account commonly prefer sowing wheat upon their fallows. Potatoes are raised in considerable quantities, and, during the winter, form a principal part of the food of the poorer classes of the people.” (OSA, Vol. V, 1793, p. 441)

Farquharson, David: The Banks o’ Allan Water, 1877. Photo credit: Royal Scottish Academy of Art & Architecture

You can really sense from reading the parish reports that there was a real understanding of what crops could be successfully cultivated and how best to grow them. For example, in Ferry Port-on-Craig, County of Fife:

“The crops that are best adapted for the clay, to produce the greatest profit, are, wheat, beans, barley, grass, and oats. Flax is sown to very good advantage; but, on the whole, it is rather an uncertain crop; it likewise produces potatoes, but the quality is generally not so good as in light soils. The strong loam stands on a whin rock; and, where there is sufficiency of soil, it produces wheat, oats, beans, barley, grass and potatoes, in great perfection. Flax is sometimes sown on this soil, but seldom proves a good crop.” (OSA, Vol. VIII, 1793, p. 458)

In the parish report for Kinloch, County of Perth, several varieties of potatoes cultivated in that parish are mentioned, including the London Lady, the red-nosed-white kidney potato and the dark red Lancashire potato. Some advice is even given on “the best method of preventing potatoes from degenerating, and of rendering them more prolific”. (OSA, Vol. XVII, 1796, p. 472)

It seems that the widest range of produce was grown in the north of Scotland. In Unst, County of Shetland, the list of what was cultivated is very impressive:

“Black oats, bear, potatoes, cabbages, and various garden roots, and greens which grow in great perfection, are the most common vegetables in this island. Artichokes, too, of a delicate taste, are produced here, with some small fruit, and most of the garden flowers that grow in the north of Scotland. There is little or no sown grass, but the meadows are rich in red and white clover, and in the seasons of vegetation, are enameled with a beautiful profusion of wild flowers. The pasture grounds, in the commons, are generally covered with a short, tender, flowering heath. Some curious and rare plants have been discovered in this island by some gentlemen skilled in botany. The common people gather scurvy grass, trefoil, and some other plants that grow in the island, for their medicinal qualities. The roots of the tormentil are used in tanning bides.” (OSA, Vol. V, 1793, p. 186)

Reay, County of Caithness, was another parish which produced “an abundance of all provisions necessary for the use of the inhabitants. The exports are in general bear, oatmeal, beef, mutton, pork, geese, hens, butter, cheese, tallow, malt, whiskey, to the market of Thurso; black cattle, sold to drovers from the south; horse colts, sent to Orkney; lambs, to the lowlands; geese, sometimes to Sutherland and Ross; as also hides, skins, goose-quills, and other feathers.” (OSA, Vol. VII, 1793, p. 575)

This knowledge extended to the preservation and transportation of food. One “adventurer” from the parish of Dyke and Moy, County of Elgin, “cured a quantity [of cod] in barrels, like salted salmon, carried them to London, and made no loss by the adventure, though they sold heavily, and must have been but unpleasant food. But had these cod been parboiled, and cured with vinegar at the boil-house, like kitted salmon, it is believed, such soused fish would have excelled the salted, as much as the kitted salmon exceeds the salted, in quality and price.” (OSA, Vol. XX, 1798, p. 209)

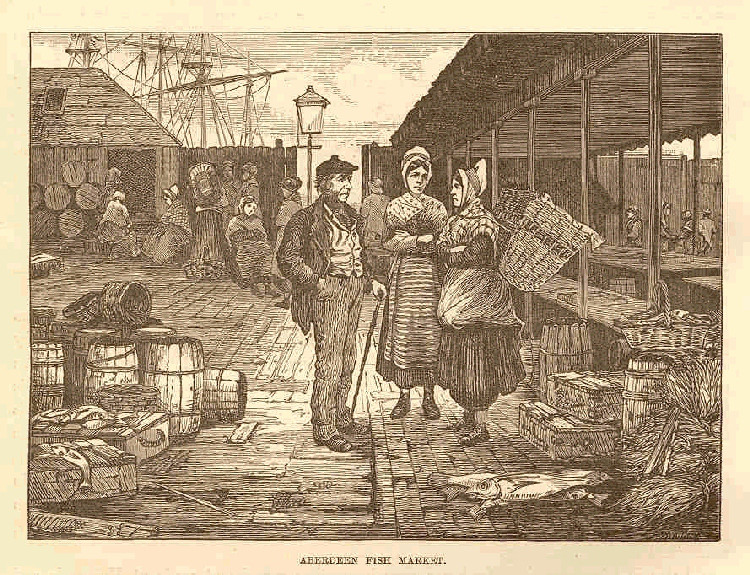

Selling of produce

In most cases, what was cultivated or reared by farmers was then sold in the large towns and cities. In the parish of New Machar, County of Aberdeen, its proximity to the city of Aberdeen was seen as a big advantage, as there was “a constant demand, ready market, and a reasonable price for every article which the farms produce.” However, it was also seen as a disadvantage, as it “renders every article sold within the parish, very high priced to those who must buy; and that the country people are so much in the way of attending the weekly market, that they generally lose one day in the week, in order to dispose of an article, which when sold, will scarcely bring them 1 s. 6 d. never considering the loss of time and labour”. (OSA, Vol. VI, 1793, p. 469)

Aberdeen Fish Market by Frederick Whymper, 1883. Freshwater and Marine Image Bank, University of Washington [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

As a result of growing and raising such produce, farmers themselves began to become more wealthy, as pointed out in the parish report for Cambuslang, County of Lanark:

“The farmer, as well as the merchant, came by degrees to relish the conveniences, and even the luxuries of life; a remarkable change took place in his lodging, clothing, and manner of living. The difference in the state of the country, in the value of land and mode of cultivation, in the price of provisions and the wages of labour, in food and clothing, between the years 1750 and 1790, deserves to be particularly recorded.” (OSA, Vol. V, 1793, p. 251)

However, not all farmers were so hard-working and successful! In a survey, carried out in 1778, it was found that the inhabitants of Auchterarder, County of Perth, were “idle and poor farmers not thinking it necessary to thin their turnip while small, allowing them to grow until they be the size of large kale plants, and then it is thought a great loss to take them up, unless in small quantities, to give to the cow. A few tenants excepted, no family had oat-meal in their houses, nor could they get any. The oat nothing better than bear-meal and a few greens boiled together at mid-day, for dinner, and bear-meal pottage evening and morning.” (NSA, Vol. X, 1845, p. 288)

Vocabulary

In an interesting aside, the peasantry in the parish Cross and Burness, County of Orkney, used “a good many words […] peculiar to the north isles, and some of them are evidently of Scandinavian origin.” Many of these words were farming and food-related. Here are the first few words given:

“Abin, (v.) to thrash half a sheaf for giving horses. –Abir, (n.) a sheaf so thrashed. –Acamy, (adj.) diminutive. –Bal, (v.) to throw at-Been-hook, (n.) part of the rent paid by a cottar for his land is work all harvest; but besides his own labour, he must bring out his wife three days, for which she receives nothing but her food. All the women on a farm are called out at the same time; they work together, and are called been hooks, and the days on which they work been-hook days. –Bull, (n.) one of the divisions or stalls of a stable. –Buily, (n.) a feast. –Buist, (n.) a small box. –Builte, or Buito, (n.) a piece of flannel or home-made cloth, worn by women over the head and shoulders. –Brammo, (n.) a mess of oatmeal and water. –Bret, (v.) to strut. –Brodend, (adj.) habituated to. –Burstin, (n.) meal made of corn parched in a pot or “hellio”…” (NSA, Vol. XV, 1845, p. 95)

(Look out for our posts on Scotland and its languages coming soon!)

Conclusion

It is clear that Scots in the countryside ate what they themselves produced, which was dependent on the climate, topography – and not forgetting knowledge and hard-work! Those in cities, such as Glasgow and Aberdeen, were able to buy this produce in markets. Increased knowledge, new technologies and the exporting of goods from other countries had seen the situation change for the better over the years.

In the next post on Scotland’s food and drink we will look at times of food scarcity, the provision of food as part-payment and the link between food and health as seen by those in the late-eighteenth/early-nineteenth centuries.